Eric Hynes | Slate

With their new IMAX 3-D spectacular Metallica: Through the Never, the multiplatinum-selling speed-metal quartet from San Francisco have devised an ambitious way to showcase their music for a new generation of fans. Rather than capture a pre-existing concert, they put together a stage show explicitly for this movie, filling an arena with more props and pyrotechnics than Nigel Tufnel could dream of and rigging up 24 cameras to give moviegoers an uncanny sense of being there for the jackhammering of “Master of Puppets” and the baroque balladeering of “Nothing Else Matters.”

With their new IMAX 3-D spectacular Metallica: Through the Never, the multiplatinum-selling speed-metal quartet from San Francisco have devised an ambitious way to showcase their music for a new generation of fans. Rather than capture a pre-existing concert, they put together a stage show explicitly for this movie, filling an arena with more props and pyrotechnics than Nigel Tufnel could dream of and rigging up 24 cameras to give moviegoers an uncanny sense of being there for the jackhammering of “Master of Puppets” and the baroque balladeering of “Nothing Else Matters.”

But there’s also something else afoot here, something to earn the film’s grandly oblique title: a wordless, surrealistic adventure narrative that was conceived by the band along with director Nimród Antal. These fictional sequences are threaded through the song cycle but take place outside of the arena, with actor Dane DeHaan playing a roadie sent on a mysterious quest through an apocalyptic cityscape. The idea is to visualize what the mood and lyrics conjure, to take the audience on a cinematic journey through the band’s greatest hits, and to solidify and expand the Metallica brand.

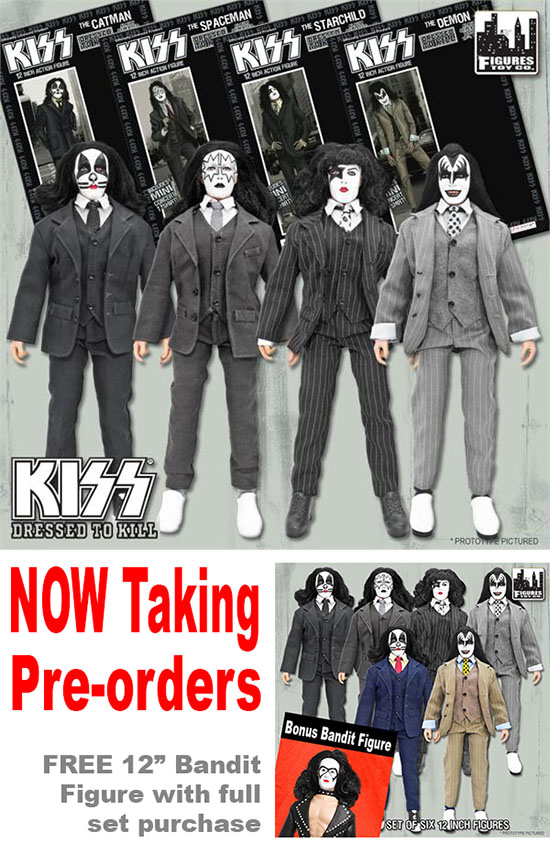

It’s been a while since we’ve seen a certifiable rock ‘n’ roll funhouse adventure film. Music videos rendered them redundant in the 1980s, though bubblegum derivations likeMichael Jackson: Moonwalker and Spice World occasionally popped up in the intervening decades. But in the prime of the mid-1970s, the era of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Saturday morning animated musical whodunits like Scooby-Doo, curios such as Alice Cooper: The Nightmare, and the venerable KISS Meets the Phantom of the Park turned rock gods into genre heroes. Fueled by synergistic pretentions and trans-media ambitions, yet saddled by inadequate production values and half-assed-at-best storytelling, these films were credibility killers that also had a kind of hubristic integrity—bridges too far that crash satisfyingly into the bay. Though it’s technically superior to any of its forebears, and serves as a sonically superlative (if also monotonous) concert film, Metallica’s batty fantastical elements have effectively awoken this gloriously inglorious genre from a prolonged hibernation.

Yet except for an opening sequence in which the hoodie-wearing DeHaan enters the arena and spies each member of the band before the show, the concert and adventure elements are kept separate. And except for a momentary fake stage disaster, in which lead singer James Hetfield utters the Keanu-worthy line “Whoa … what’s going on?” the band members are never obliged to act in the film. Judging from Lars Ulrich’s brief cameo in Get Him to the Greek, this would seem to be for the better. But what, pray tell, is the point of making a Metallica musical adventure film, one in which a gas-masked horseman of the apocalypse lynches street protesters from streetlamps, if you’re not going to dress up bassist Kirk Hammett as a zombie policeman, or have Hetfield shoot perforated laser beams out of his eyes?

Oh, right: because KISS Meets the Phantom of the Park was a work of such cautionary folly that only Michael Jackson was crazy enough to attempt anything like it. This made-for-TV camp landmark, in which the aforementioned perforated laser beam was employed, was the simultaneous apex and nadir of glam rock outfit KISS’s career. It was the second-highest-rated televised event of 1978 (behind only Roots) while also inexorably contributing to the fracturing of the band/brand. After the purportedly tedious shoot at California’s Magic Mountain amusement park, each member hustled together poorly received solo albums, drummer Peter Criss spiraled deeper into substance abuse and would soon be replaced, guitarist Ace Frehley’s disaffection would lead to his own exile, and the band’s spiraling discomfort with their own identity would lead to such desperate measures as a synth-heavy prog rock concept album, and the shunning of their trademark makeup masks.

Yet Phantom had a transparency of purpose that Metallica: Through the Never labors to obscure, not to mention a levity that Lars and co. are too busy bench-pressing their own mythology to entertain. I won’t make any claims for Phantom’s quality—it has “cheap, uninspired quickie” written all over every haphazardly framed shot—but 35 years later it remains as disarmingly loopy as it was on broadcast date Oct. 28, 1978, the Saturday before Halloween.

The movie starts with a title sequence in which the four members of KISS—Gene Simmons, Paul Stanley, Peter Criss, and Ace Frehley—materialize in an amusement park as towering, platform heel-wearing holograms to sing “Rock and Roll All Nite,” only to disappear from the telecast for 30 whole minutes (not counting commercials). In the interim, we meet Abner Devereaux (Anthony Zerbe), a vaguely European mad scientist type who toils beneath the park, and whose experiments in animatronics have secretly branched into human abduction and mind control. When he sees park financing redirected into KISS’s hotly anticipated engagement, Devereaux plots a hostile, vaguely explicated takeover involving an army of albino wolfmen in silver onesies and KISS’s evil android doppelgängers.

Gene Simmons recently rated

Gene Simmons recently rated

AXS TV

AXS TV After having run a very successful PledgeMusic.com campaign that reached 241% of its stated goal and raised just under $23,000 for the Vaudreuil-Soulanges Palliative Care Residence in Hudson, Quebec (

After having run a very successful PledgeMusic.com campaign that reached 241% of its stated goal and raised just under $23,000 for the Vaudreuil-Soulanges Palliative Care Residence in Hudson, Quebec (

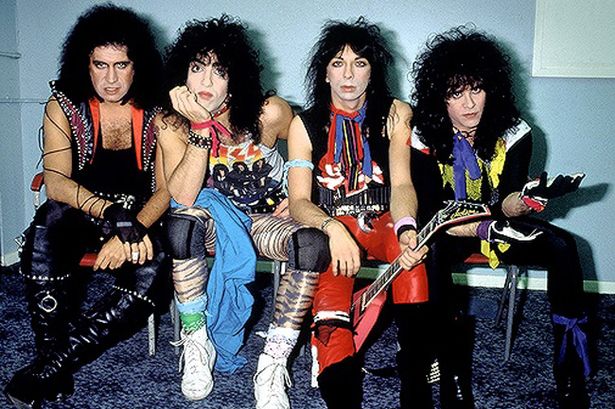

They were the rock stars dressed like Marvel comic book heroes who took America by storm – and a band which also made waves here in the UK.

They were the rock stars dressed like Marvel comic book heroes who took America by storm – and a band which also made waves here in the UK.

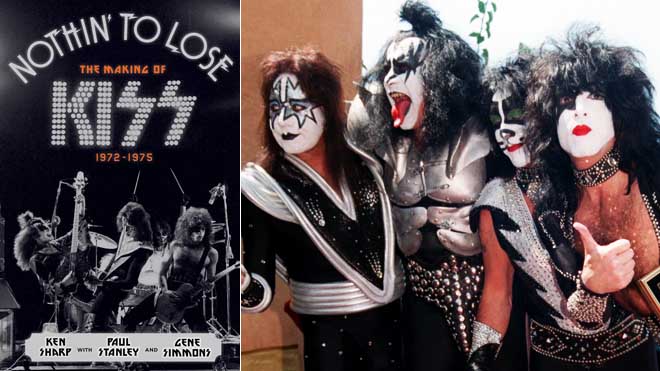

Legendary KISS founders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley have collaborated on the memoir ‘Nothin’ To Lose,’ an oral history of their rock band’s genesis. “It’s an overview of the band,” explained Stanley. “How it came about from its inception, almost from the time the sperm fertilized the egg really.” Indeed. FOX411 spoke to both Stanley and Simmons about the book, their football plans, and what went wrong with original KISS members Peter Criss and Ace Frehley.

Legendary KISS founders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley have collaborated on the memoir ‘Nothin’ To Lose,’ an oral history of their rock band’s genesis. “It’s an overview of the band,” explained Stanley. “How it came about from its inception, almost from the time the sperm fertilized the egg really.” Indeed. FOX411 spoke to both Stanley and Simmons about the book, their football plans, and what went wrong with original KISS members Peter Criss and Ace Frehley.

UD Replicas

UD Replicas