Tim McPhate | KissFAQ

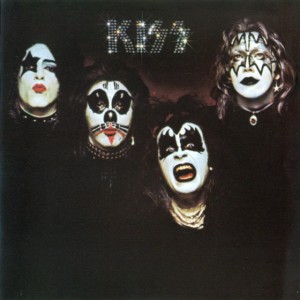

Imagine being a fly on the wall at Bell Sound Studios in 1973 while KISS were recording their debut album. Imagine listening to playbacks of takes for songs such as “Strutter,” “Deuce,” “100,000 Years,” “Nothin’ To Lose,” and “Black Diamond.” Imagine the decibels of raw, primal KISS power reverberating throughout the studio.

Imagine being a fly on the wall at Bell Sound Studios in 1973 while KISS were recording their debut album. Imagine listening to playbacks of takes for songs such as “Strutter,” “Deuce,” “100,000 Years,” “Nothin’ To Lose,” and “Black Diamond.” Imagine the decibels of raw, primal KISS power reverberating throughout the studio.

Now, imagine being a musician and having an opportunity to get in on the fun and literally play on the album.

Grammy-nominated musician Bruce Stephen Foster enjoyed the latter privilege. A “hot-shot young piano player” at the time, Foster has the distinction of being the first outside musician to play on a KISS studio album. Co-producer Richie Wise felt a musical element was missing in Gene Simmons’ ode to back-door lovin’, “Nothin’ To Lose,” and he knew just the guy to call. Enter Foster, who ended up contributing a complementary old-time rock and roll-flavored piano track, adding the perfect layer to what would become KISS’ debut single. The part did come with a price, however.

“I wound up with my fingers bleeding,” jokes Foster.

Foster would be properly acknowledged for his work in the album’s credits, perhaps due to KISS being a new entity at that point. Interestingly, this particular credit stands as an anomaly in the KISS catalog given the several ghost musicians who would appear on later works.

KissFAQ caught up with Foster to ask him about his recollections of the “Nothin’ To Lose” session and working with KISS. The New Jersey-based musician also shared some fun stories and briefed us on his longstanding career in the music industry, which continues to this day. But before we get to the interview, read below a personal introduction from Foster:

It always amazes me how time is such a relative entity. Listening a moment ago to “Nothin’ To Lose'” felt like a fresh memory…not one from way over 30 years ago! I remember honing my piano part down to the measures of music that would make it count artistically. A creative pool of talent gathered in the studio that day helped me massage it into

something that made a subtle statement of added excitement woven into the track. It fits the old phrase “brief but meaningful” very well. When I left the studio that day I wished the best for the group knowing the odds for real success are slim. Having a hit is like winning the lottery…no matter how good you are. Months later I realized what a great marketing team Gene and Paul were. Add the brilliant Neil Bogart to the equation and the sky became the limit. The thing that still amazes me the most is how people can read my bio and see all of the hits I’ve been fortunate to be involved with, a Grammy nomination, writing songs with and for some of the legends of the industry…but the only response of awe that I EVER seem to get is, “Wow, you played with KISS?!!!”

I’m forever thankful to have been a tiny part of rock and roll history and to know I can still rock and roll all night and party every day.

Love to the KISS fans of the world,

Bruce Stephen Foster

9/13/12

KissFAQ: Bruce, “Nothin’ To Lose” is notable for not only being KISS’ first-ever single, but also the first KISS song to contain an “extra” musician. Prior to your session with KISS, what was your status as a musician in 1973?

Bruce Foster: At that time I had just come off the road playing with Buzzy Linhart, you know one of the world class maniacs in the music industry (laughs). The band consisted of Steve Mosley on drums, who at that time had been playing with the David Blomberg Band and many, many other things; Hugh McDonald on bass, who for many years has been with Bon Jovi; Steve Berg, who produced a lot of folky rock acts and produced something for the Ramones, he [also] had his own recording studio later on; and myself on 12-string rhythm guitar, sometimes lead, and mostly keyboards.

Steve Berg had come out of a band, along with Steve Mosley, called Jacobs Creek, that was on Columbia Records a year or two before that. And Hugh McDonald had been a neighbor in New Hope, Pennsylvania. We all wound up playing together, the four of us. So we had just come off the road doing that.

KF: How did you end up getting involved with KISS?

BF: The other guys ended up hooking up with Richie Wise, who was part of Kerner and Wise, the production team that produced the first two KISS albums. I wound up getting involved and playing on some Gladys Knight albums right around that same time, within months of that. And Richie Wise, other than hearing me playing kind of soul piano stuff for a recording by Gladys Knight, knew I could sort of rock out like Jerry Lee Lewis and all of that and thought that I might be perfect on [“Nothin’ To Lose”]. So he called me in for the session and of course that was among KISS’ first recording sessions. It was really just Richie Wise, Kenny Kerner and Warren Dewey, who was very, very instrumental in creating the basic sounds that initiated the first two KISS albums. Warren had gotten every award there was available to give to an engineer for work he did between that, Gladys Knight and Earth, Wind & Fire, and many, many other things. So it was a good team.

KF: KISS’ debut album was recorded at Bell Sound Studios in New York. What do you remember about the studio and the recording environment?

BF: Well, Bell Sound, I had been there several other times in the few months before doing Gladys Knight songs. The grand piano was on the far end of the room, away from the glass that separated the recording room from the console. It was a Steinway piano, as most old studios had in those days. A lot of the studios in the mid ’70s, shortly after that, and in the ’80s started going over to Yamahas. Mostly because the Yamahas didn’t have to be tuned as much and they were a little brighter for the sound. I mention that for any piano players out there because the old Steinways, man, it was like pushing down on a ton of bricks. It was really stiff action on those things. They were made for classical musicians that had powerful fingers, you know these are guys who practiced 12 hours a day. It was all part of the restraint and momentum that needed to be had all at the same time. Therefore, when I’m trying to play a Jerry Lee Lewis kind of sounding thing on “Nothin’ To Lose” on this old Steinway, it was getting very tiresome. And we experimented with a lot of different approaches. And it really did take — you know something that seems like I should have been able to walk in [and play easily because] it’s such a simple part — but we experimented. Richie Wise made some suggestions and said, “Let’s try this and let’s try that.” And some of the Jerry Lee Lewis glissandos that I added, because of the stiffness of the keys, I wound up with my fingers bleeding. (laughs)

So the most striking thing I remember about that session is Gene Simmons coming in, and Paul, very briefly, he popped in. He didn’t really hang out in the studio much. But Gene came in and saw blood all over the keyboard. (laughs) And he had a satisfied, bemused look on his face, like, “This is cool. This is perfect for this album.” So he seemed very pleased with it.

KF: That does add an appropriate element. It’s funny you mention Jerry Lee Lewis, because your piano definitely adds an old-time rock and roll texture to the chorus. How did you prepare for the session? Were you given a recording of the song prior to coming in or in those days did you just come in and go for it?

BF: Yeah, that was really exactly it. And it’s funny, that style of playing, one year before I had been in England doing a very strange project I was a vocalist on. It was a very famous Italian album by Fabrizio DeAndré, who was sort of like the poet laureate in Italy at the time. He was a cross between Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen and he had this piece called the “Cantata Of Social Comment For Solo Orchestra And Chorus In Bb Minor.” And I was elected to do the English-speaking version of that. It was a big, big production, “End of the world, we’re all junkies, there’s no god, the only mercy is in death.” The most depressing album ever frickin’ made, so it never really got released in English-speaking countries but it was huge in Italy. And that led me to playing with the group Status Quo while I was there because I was in the studio one night doing all my Jerry Lee Lewis stuff. Status Quo was one of the biggest groups ever — I think in the pecking order, it was the Beatles, the Stones and Status Quo in England. So that Jerry Lee Lewis stuff got me a lot of gigs; I wound up playing on one of their albums also just the year before.

I think a little bit of the press and promotion was getting around about me being a “hot-shot young piano player.” So the vibe was good in the background, I already had some pretty good credentials. That was kind of the shoo-in to get in on that initial date. And it’s just one of those things that happens when you’re young and you’re at the right place at the right time. And I was very, very lucky that way. I have to say I’d rather be lucky than good and damn I’ve been lucky.

KF: Did you track any piano for the verses of “Nothin’ To Lose,” or was it strictly a matter of embellishing the chorus?

BF: I think that initially Richie Wise said, “Let’s listen a couple of times and go out and just overplay. Play anything you want. Any nuance, anywhere that you hear a hole that you think should have some piano.” And I tried a whole lot of different approaches in the verses, the choruses and after you take a step back on a playback and listen. You know I would go in and we would all discuss it together and just say, “No. Of course that’s way too much. But are there any parts that we want to salvage that stick out that [might] become a hook for the song?” And after doing that for maybe an hour, the consensus was, “No, it seems to work perfectly in those choruses and that’s all it really needs.” Subtlety says more than anything else, which is really the rule in the art of making records. I think that one of the reasons that people that were the Juilliard grads and the jazz college grads from Berklee, etc., were wondering why they couldn’t get more recording work is because they’re too good. (laughs) They tend to overplay, they tend to hit chord clusters that are too thick for the song. And the whole thing in playing rock and roll especially, when you grow up just knowing that genre so well, you realize the space is just as important as the notes.

KF: Absolutely. Part of the appeal of KISS is simplicity. The chorus for “Nohtin’ To Lose” just alternates between A and E chords. There’s only so much you can do there.

BF: Yeah, and it was just a thing of taking it from the quarter notes into eighth notes. And it just picks up the pulse [sings quarter-note rhythm then sings eighth-note rhythm].

KF: I take it you didn’t play live with the band?

BF: No. To date I have never met the original drummer or lead guitarist. (laughs)

KF: Peter Criss and Ace Frehley.

BF: Right. Gene was the guy that was really the main spokesperson. Paul gave a few nods of approval and was obviously on his way to do something else. Gene hung around a little while longer. It’s really funny, by the time they ended up doing their second album I sat in on a couple of sessions and there was speculation that I should play on something there too. I think KSS at that time decided that they really needed to be self-contained. They didn’t need anything else on [the album]. And it was a mutual consensus. I listened to some of the stuff at that time and I said, “No, I really don’t hear it. It’s pure the way it is. Don’t fix something that’s not broken.”

KF: The second album was “Hotter Than Hell,” which is a bit heavier than the debut. Now that you mention it, in hindsight, there may be one or two songs on there that could have used piano.

BF: If I had played any keyboards on the second album, my suggestion and everyone’s immediate agreement was that it wouldn’t have [been] piano, it would be an organ — a very nasty distorted B-3. That could have really done something. But then again it would have changed the whole vibe. They went for the purity, they did the right thing. But it was fun seeing Gene again. The first thing that he did when I walked into the studio where they were recording the second album, was he said, “Hi Bruce,” and took both of my hands and looked to see if my fingers were still bleeding. (laughs) And he did that for years after that, that was like his running joke. I’d run into Gene in a deli in Los Angeles and I guess he was probably working that time at the Record Plant. Richie Wise had moved out to the West Coast by that point. In fact, I’m wondering if the second album was done in California?

KF: It was. It was at the Village in L.A.

BF: It was Village Recorders, right. OK. I was getting a different mental image. It was that period where I wasn’t quite sure because I had one foot in New York and one foot in L.A. I did a lot of work at Village Recorders at that time on other projects with Richie and other people. That’s where it was. And after that, KISS wound up doing a couple of things at Record Plant, which I was also at intermittently for other projects.

KF: When you listened back to the final track of “Nothin’ To Lose” for the first time, do you remember being satisfied?

BF: Oh yeah, extremely. The thing that somebody like me looks for in a final product is making sure that my timing is perfect for one thing. Playing something like eighth notes, it’s so simple that it’s very deceiving at how difficult it is to lock into that simplicity and play. If you’re a musician or there any musicians reading, you can be a little ahead of the beat, you can be right on the beat, or you can be just a little behind the beat. And you have to really gauge the song and see which one of those things you have to lean to. It’s either going to be right on or maybe you should push it just a little bit because that adds excitement. And that’s a whole thing unto itself. It’s like a nuance that only people who make records are usually aware of but the listener just absorbs the impact.

I was like, “Yeah, that’s jammin’ you know.” I know it was the first thing that they ever got on the radio. I thought at that point, “Well, I’m probably in this band now.” (laughs)

KF: So this session would have taken place in just a single day?

BF: Yeah, that was just done in a few hours.

KF: Was that the arc of a session for you in those days: You got in and did your business and got out?

BF: Yeah, you know if it had been an original thought instead of an afterthought, I’m sure that I would have been there playing on every track that they had cut for it. I believe they had done many takes on that, finding the right groove, etc., etc. And it was the days when you would just get 10 reels of tape and just tell the band to keep playing, and you recorded everything in those days, because you didn’t want to lose the one thing that would be magic.

KF: How many passes do you think you took at your piano part?

BF: Oh gosh, I would say it would probably would have been 10 or 15, all in all. You know, “Let’s try this,” and the producer really guiding me through and saying, “Raise it up an octave at the end. Or try adding the left hand on the bottom. Let’s listen one time without the left hand in.” And as I recall, it may have a little bit of a left hand thing going on way down deep. And if it’s played really precisely you won’t even notice that it’s there but it just adds a little bit of gravity to the bottom and all of the sudden gives a little more oomph in the track.

KF: In terms of compensation, was this a union gig or under the table?

BF: No, I was with the Local Musicians Union 802 so everything had to be done through them in those days. The pay was quite good. You know, [for] a three-hour session, there was a flat rate or something like that. It was somewhere around maybe $1,200 for the three hours. In 1973 it was pretty good.

KF: Nice work if you can get it.

BF: Yeah, it was really wonderful. You know those were very good days because every two weeks I was out in L.A. I’d be two weeks on the right coast, and two weeks on the left coast. So that really became, and still is, my other home.

KF: Later in KISS’ career, there would be several musicians who participated in a ghost capacity. However, you were actually credited on the album. Do you recall specifically requesting the credit?

BF: To me, it was really protocol and expected. At that time, don’t forget, KISS was completely an unknown entity. And I had already had, you know since I was 16 years old and signed to Columbia Records, I had already had a little bit of a track record and somewhat of a career so I was kind of like, I mean it seems silly looking back now, but I kind of had a little bit of more gravity than they did. (laughs) LIke, “Hey, we got this guy on this and he’s done this and that, you know, and Status Quo.” People in the industry knew how huge they were, they just never had a hit in America. So I think in a case like that they thought maybe it was a boom to have my name on the album. (laughs) Which is interesting, because on the Gladys Knight stuff that we did — and I played on four Gladys Knight albums and a couple of them were huge albums, you know platinum albums — not only did I ever get a gold record, but we were never credited on her stuff. And that was not because Richie Wise didn’t put our names down, it was between Gladys and the record label I guess.

KF: I believe she was on Buddha Records at that time, which was Neil Bogart’s label. And of course, Neil then started up Casablanca Records.

BF: Yeah, I think KISS were the first artists on Casablanca.

KF: Yes, indeed.

Richie Wise: When is the last time you’ve spoken to him?

BF: Well, I’ve been thinking about calling Richie this week, isn’t that funny? I spoke to him a few months ago and we are still the dearest, dearest of friends. After all those years, about 10 years ago, Richie and I decided to do a project together. It was my solo album, which has still never been released but that’s another story. (laughs) It’s called “Reality Game.” But he said, “Man, I’d always love to record you as a solo artist.” So we finally did it. And it was a really, really beautiful coming around of the circle. Richie is kind of out of the music industry right now. I mean there’s no industry to be in, let’s face it. He was one of the smart ones and he wound up getting into a very, very good job. [He] just saw it was really the end of the record companies and all that. And he’s amazed that I’m still in the music industry and still slugging it out there everyday, getting occasional sessions and producing for artists, etc.

KF: Getting into your career, Bruce, you’ve released solo albums and collaborated with artists such as Cher and Richie Sambora, among others. How did you get to know Richie Sambora?

BF: Interestingly, I was playing at a club in East Brunswick, New Jersey, called Charlie’s Uncle (laughs). And my bass player that night in the band, and we were playing mostly originally music, my bass player got food poisoning so he was on his way to the hospital. And I climbed back up onstage — we were only a trio that night, it was the drummer and I — and I kiddingly said, “Well, is there a bass player in the audience? Mine is wretching in the parking lot.” Richie Sambora was 18 and was in his first semester at Kean University in New Jersey, right nearby where he lived in Woodbridge. And Richie was sitting like literally five feet in front of us at a table and he said, “Hey, I’m a guitar player, I’ve never even held a bass, but I’ll give it a shot.” (laughs) So I said, “Come on up, Richie.” And I’m not the kind of guy that ever lets people jam. I’m really not into that. But there was something, you just had to like this guy immediately. So he came up and he picked up the bass and he was trying to figure it out. He didn’t even know what all the notes were on it and how it was tuned compared to a guitar. It took him a couple of seconds to figure out it was the first four low notes of the guitar. He had no concept how to play and he was terrible and every time he made a really awful mistake, he’d look up and just kind of laugh. Instead of getting nervous, he’d put you at ease. He was so charming and after that very brief set we did, he said, “Hey look, I know I sucked on bass but I’m a really good guitar player and I’d like to redeem myself as a musician if you would just let me bring back my guitar and show you that I really can play.” And I said, “OK. Bring it back next week.”

Well, the next week he came back and he had his beautiful little Les Paul custom guitar and a mini Marshall. And I said, “Alright, come up with it.” And we did “Kansas City,” and that’s a song that everybody knows. You can’t go wrong with that — it’s three chords [and a] blues thing. And his rhythm was cool so I said, “OK, Richie you take a solo.” So I was really expecting him to really break out and try to impress me and do a million-note hot dog solo. Instead, he hit the toggle switch on his Les Paul custom and he went [sings bent note] and he bent this one note that sounded like a cross between Jeff Beck and Jascha Heifetz on the violin. Before he hit the second note, he had such finesse and he had such control that you knew that instead of trying to impress me with a million notes that this was a guy that knew what content was innately. He had something and I knew it in a second. Before he hit his second note, I said, “You’re in the band.”

KF: That’s a great story.

BF: From that moment on, he played with us the rest of the night. We had a rehearsal next week, he was in the band [and] we did that for about a year and a half. I had just had my first solo album out, just before that, that crashed and burned. That was also with Neil Bogart as Casablanca [was] the mother label to Millennium Records.

KF: That would have been your “After The Show” album in 1977?

BF: Yes. So this was now ’78, and Neil Bogart at that time I guess was already having his cancer problems. And the word I was getting, was squandering a lot of the money instead of putting it into promoting the artists. I guess he knew he was dying and he was going and spending his money in Las Vegas, gambling and stuff. It was a whole crash-and-burn thing that I unfortunately became a part of. The album and the label kind of went down in flames so I was back in the clubs trying to regroup and that’s where we met Richie. And we put together Shark Frenzy, which is finally available on the Internet at this point. There’s two albums, like 30 songs that we recorded in that year and a half. It’s the very first things Richie ever wrote, played on in a studio and certainly sang lead on. So it’s wonderful archival stuff and you can really hear how brilliant Richie was as a young player, you know he was 19 or 20 years old by that point. I think that his first work with Bon Jovi happened around ’80 or ’81. That’s why Shark Frenzy really had such a short run because he had had one foot in Bon Jovi anyway and all of the sudden they started you know… (laughs) They got the album deal, they got everything happening. And Hugh McDonald, interestingly by the way, was playing bass on all of the Bon Jovi albums.

KF: That’s right. Like we were talking earlier with KISS, he was playing in a ghost capacity.

BF: Right. He was always really the Bon Jovi bassist. And Alec [Jon Such] was the live bassist and the buddy that went to high school or whatever with Jon, and grew up in the neighborhood. Which was wonderful of Jon to keep it together like that. Alec was quite capable of playing all of the parts live but when it came down to creating in the studio, let’s face it, at that point Hugh McDonald probably had six years of real studio playing under his belt. I think the second Bon Jovi album is the only one that Hugh does not play on. That’s the only one where you’ll hear Alec.

KF: “7800° Fahrenheit.”

BF: Yeah. So Richie Sambora and I remained dear dear friends, went through a lot of projects together through the years. And 20 years ago, on his first [solo] album, we wrote a slew of songs, two of which ended up on the album, “One Light Burning” and “The Answer.” On his new album, which comes out literally in a day or two, called “Aftermath Of The Lowdown,” I co-wrote the final song on the album, which is called “World.”

KF: Very cool. Is that an older song or a fresh composition?

BF: We started it when he was still with Heather [Locklear] about eight years ago. I remember we stayed up one night writing that until dawn. So that was the beginning of it. And he had been planning on making a solo album for all of this time but you know the resurrection of Bon Jovi was so powerful that there was no time for him to finish anything. So he had to put any solo career on hold. And let’s face it, when he’s with Bon Jovi at this point, who needs a solo career? (laughs) It really just took that long to come around to finally having the break to put out the album and go on a mini tour — he’s got a couple of months now to do that to promote everything, which he did not have with [his last solo album, 1998’s] “Undiscovered Soul.” I think he may have a really good shot on this. We continued about three or four months ago, kind of tweaked the song. I went out to L.A. and stayed a couple of days at Richie’s and we just wrote and wrote, and worked on “World” and a couple of tunes that fell through the cracks. (laughs) You know, you’re always hoping you’re going to have like three things on [an album] but Richie was in good company. Bernie Taupin worked with him on one of the songs, I can’t wait to hear that because Bernie Taupin is just one of the greatest lyricists of all time. So it’s an exciting project. [The song] was our love letter to the world.

KF: You alluded to the state of the industry these days, but you’re still out there plugging away.

BF: Yeah, well thank god for residual income. Because I still get residuals on about, I guess a dozen things out there. And all put together, it would maybe only pay a months rent at this point. So anytime you get a new shot in the arm, like what’s going on with Richie’s album. I could make nothing or very, very little off it, or it could be something that gets used for World Day or Earth Day. You know, it could be one of those anthemal things that all of the sudden generates some income. So you really hope for that free money to fall out. You know every once in a while something happens when you open up the mail and there’s something from ASCAP. I got a song in “Days Of Thunder,” and “Days Of Thunder” was playing big on cable so I’d be making some money on that. “Stayin’ Alive,” I had a song on that called “Look Out For Number One,” which actually had a Grammy nomination. Every time something like that happens, it keeps you in the business another few years.

And it’s funny, I remember Paul Simon being asked in, what I would consider the peak of his career, back in the late ’70s, “For musicians like you who have made it, do you have any advice?” And he said, “Well, wait a minute. How do you define ‘have made it?’ I’m not sure whether I’ve made it.” And here’s a guy, he got a Grammy every year. And it’s all so relative. On someone’s scale like mine, I look at someone like him and just say, “Well that’s about as much making it as you can.” You’re just staying in the business and that’s all you do is music. And I realize now, looking back on my life, how lucky I’ve been that all I’ve ever had to do is music and I’ve done all right. I’ve never gotten rich. You know, Richie lived on the other side of the river from me. I’m in a nice little town called Oceanport here in New Jersey. It was one of the best decisions I ever made. It’s like living in a park here. It’s just gorgeous and I’m looking out at the river right now across the street from me, I’m not on the river. But when my neighbors with their 40-foot high house that looks like a sand castle across the street don’t have their two massive SUVs parked in tandem, I can actually see the river. (laughs) And for several years, Richie lived right across the river. And we lived that dream. When we were in Shark Frenzy together, just before Bon Jovi broke and all of that, I had already bought my house when I was 22 years old. I was lucky, and thanks to Gladys Knight and KISS and all those sessions, I was able to get the down payment. And when Richie used to come by and see me here, he would say, “Man, wouldn’t it be great if I made enough money eventually in the business and I could get a house right near you? Wouldn’t it be great to be neighbors, man, and hang out?” And sure enough within 10 years of that, he had a house in Rumson, which is where Springsteen and Jon live. (laughs) And I can see his house from mine. It’s funny because after he became a neighbor, I almost never saw him because he was always on the road.

KF: It’s pretty cool that you guys have maintained a friendship for all these years.

BF: You know, having friends like Richie is one of the blessings in the universe, because I’ve got to say I’ve never heard anyone say a bad word about Richie Sambora. He is one of the most true stand-up people that was ever created on this Earth. He’s just a good guy with a big heart. And he’s a brilliant guy. You talk about sticking by your friends, man, he stands by his friends.

KF: Bruce, how about a Gene Simmons story to take us out?

BF: I wanted to end up my solo album, “After The Show” on Millennium/Casablanca, with my favorite inspiration song, even though it was a rock and roll album — Billy Joel-ish rock and roll, let’s put it that way. I wanted to end it up with “When You Wish Upon A Star.” It was my favorite song of inspiration, I always told people to listen to the words and your life will be just fine. And I ended up every night singing that. And before I could record it, I found out that Gene did it on his solo album. He was recording just around the same time I was. And they said, “Guess what, we just heard that Gene did the same song.” So I saw him backstage at Madison Square Garden after a Billy Joel concert and I said, “Son of a gun. Do you know what you did?” Let me tell you, Gene is a funny guy, or was at least in those days. I haven’t spoken to him in 15 years now. He would always say a one-word answer to anything that you were saying that would put you on the floor laughing. Very, very brilliantly witty guy, aAnd he would find that one or two words. So he was usually really on, but when I saw him, I said, “That was always my favorite song.” And he got so sincere and he said, “You know, Bruce, isn’t that true though? When you wish upon a star, your dreams really do come true.” He was with Cher at the time, whenever that was. And I said, “Well, that’s easy for you to say. I’ve always wanted to f*** Cher.” (laughs) And he just fell to the floor. That’s the only time I ever got him.